From childhood experiences to cultural influences, Baum was a writer who was inspired by his changing environment. As a child, Baum learned about many fairy tales, but disagreed with the way they were told. He sought to develop a new type of fairytale, just as the world was changing. The early 1900s was an environment were many different dreamers brought their inventions to life, from Ford to the Wright Brothers, to the Colombian Exhibition, many people were motivated to create new ideas. This revolutionary way of thinking is represented in Baum's Oz books. It is a work that represents the advancements in technology, with major emphasis on color illustration. Publishers, of the period, could not visualize a book with color illustrations because they believed it would be too expensive. Although Baum knew how to print his own work, he still needed a publisher to produce copies of his work for the masses. Is it interesting to note that Baum and Denslow has to place their own money and supply their own printing plates for production. The publishers of the period only provided the distribution of books, which included ink and paper and the binding. The positioning of a title is important because it can suggest which edition of the book a person owns, especially when many copies are sold. The fact that Baum went through so many different publishing houses shows that they were popular business in the 1900s. Baum, as a writer, struggled with many people as he was preparing for his sequal. Between arguments about copyright laws with first illustrator Denslow, and publishing houses that were catering to other authors, Baum quickly learned about the publishing buisness. He learned never to shaare his rights, and to start with a new publishing company that would focus on his work. Learning about Baum's personal life, as well as the culture that surrounds him, provides different reasons for his depiction of women in the Land of Oz and the Oz series. Baum's work is important to American history and with the encouragement by children, he helped restore childhood fantasy literature. Through this book study, I learned that many elements go into the production of a book, such as printers, illustrators, authors, actors, composers, and filmmakers. The story behind the Land of Oz showcases a worldvirew, where characters go on a quest for thier own identity. This series bridges many diffrent generations, and it will always be a timeless classic for children.

Friday, April 20, 2012

Tuesday, April 10, 2012

Colophon

Colophon

The Land of Oz is a printed book, and the colophon is not located at the end of the book, but rather in the front of the book. The colophon includes everyone/place that was involved in the production of the book. The author's name L. Frank Baum, The illustrator John R. Neill, the publishing company The Reilly & Lee Co., the place of publication is Chicago, the comedians from the play version of The Wizard of Oz are mentioned as Montgomery and Stone, and the previous book title The Wizard of Oz is mentioned. The author's note includes the children who inspired Baum to continue to expand on characters and write another Oz story. These children can be included as part of the colophon. This is a record of information that highlights young readership of the 1900s. The fact that many children enjoyed Baum's stories suggests that there was a need for fantasy stories in America.

Each colophon is decorated by a boxed outline, which helps highlight the importance of the information. The copyright date is decorated using ink and pen, but the decorations include what appears to be a wallpaper designer, and small babies wearing glasses/goggles?. The babies have wet hands, and are playing with some stuff on the floor They look as if they are helping the wall designer post the advertisement for Baum's copyright date, but they are not dressed as a child would dress for cleaning. The children look prosperous, as they are wearing sailor dresses. One baby/toddler is reaching into a bucket, which could be water. The adult man is looking up at the sign, (including the copyright date and authors name) and is holding a brush.

On the author's note, there is an older child reading paper and sitting on top of mounds of letters. There is ink spilled below the page. This highlights the amount of letters that Baum must have received from children asking for him to continue writing stories. In the dedication page, is a pen-and-ink drawing of the scarecrow and the tin woodsman, played by two comedians David C. Montgomery and Fred Stone. This is showing simple gratitude from Baum, for their acting in the stage play of the Wizard of Oz. Why did only these two actors get a dedication from Baum? What about Dorothy's actress, or the cowardly lion? Baum's dedication page only focusing on Tin Woodsman and Sacrecrow could be a marketing strategy. Since the sequel focuses on the Tinman and Sacrecrow's further exploration, having them in the opening pages would set up the story.

Pagination/Collation/Rubrication

Oz Book Collector

Michael O. Riley is a collector, binder and book restorer who has analyzed and worked on a large number of copies of the Hill editions of the Oz books. In his book, A Bookbinder’s Analysis of the first Edition of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (2011), he observes the Wizard of Oz (1904) printed book, and raises the question whether there could be some pattern to the manufacture of “mixed” copies, and what is the legitimate representation of the book at the point of production. There is no original “first edition” copy, so it is hard to compare additional copies to the real thing. How can a book collector determine whether his/her copy of the Oz book is closest to the original edition?

According to Riley, it has been hard to find an Oz book in mint condition, which is strange because it played a huge part in American history. There are no known copies to exist that are in perfect condition.The first edition of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is extremely important to the history of the American children’s books. Nothing like it had been seen before: its innovative design literally changed the look of books for children. It is known as having an influence on children’s book design. The sequel continues the tradition of adding color to illustration, but there appears to be problems with binding due to this artistic idea, as discussed below.

The Wizard book was considered a “trade book”, and was bound largely by the usual methods used for trade books of the time. All Oz books were hardcover books.

The text block consisted of seventeen gatherings with numerous text illustrations in color, plus twenty-four (16 for Land of Oz) tipped-in, full-color illustrations printed on art paper somewhat thinner that that used for the text.

The gatherings were machine-sewn together (Smyth sewn).The Smyth sewn technique is where the signatures of the book are folded and stiched through the fold. The signatures are then sewen or glued together at the spine to form a text block. The problem with this technique is that the pages are not secure, and will become loose over time (Parisi, p. 8).

The spine was lined with mull (a heavily starched, cheese cloth-like material) with a paper strip over this; and cloth head and tail bands were glued onto the ends of the spine. The completed text block was then glued by the mull, and (unlike the usual trade method) by the first and last sheets of the text paper, into a pre-made cloth cover (Riley p. 9).

W.W. Denslow’s innovative design in Wizard of Oz , caused some slight deviations in the text block from the trade book norm. The physical books of the period were non-standard size—being shorter and squarer than was common—and their lack of separate inserted endpapers. (Riley, p.9)

The height of the text pages (8 3/8 after trimming) meant that the Smyth sewing matching was unable to be set to sew as many stitches as it would on a standard sized volume. Wizard fell just short of the book height that could be sewed on five locked stitches. In other words, the fifth stitch could not be completed, and this left the bottom inch-and –a-half of the spine unsupported by sewing.

One of the most common ways to hold a book open for reading aloud is to hold it at that point of the spine. However, the bindings of the Oz books appear to be weaker, so they would be less sturdy with wear.

The usual trade book contained separate endpapers made of a heavier weight paper than that used for the text; and although this fold of paper was glued to the text block only along its fold, its presence did help relive stress on the weaker text paper. The Hill edition instead used the first and last text pages as the endpapers, again slightly weakening the binding. Riley believes this may have been Denslow’s decision because it allowed him to begin his design for the book on the front paste-down and to carry that design through to the last visible page, the rear paste down. When readers open the book they see the grey and black picture of the Cowardly Lion on the left and a blank page on the right, the. (Riley p.10)

The Wizard book was printed on heavy paper—too heavy for the standard method of case binding—and so, over time gravity has cause the text block in most copies to sag and loosen from the case (10). The text sheets were printed in an arrangement that caused the gatherings to be folded against the grain. The grain in Wizard runs from the gutter to the force edge rather than from the top to bottom. Because the pages do not bend as easily as they might, every turn of a page puts extra strain on the spine glue and the sewing.

WizardMost trade books of the time had gatherings folded against the grain (Riley, 10).

The book's unusual dimensions (large format) caused a problem for the standard sewing machines and made the spine connection weaker at the bottom. In order to keep the colored illustrations from showing through the paper, a heavier text paper was needed. The illustrations were in great detail, so the color plates had to be printed on coated paper and were used as inserts. This is why many Oz books need repair work or restoration.

Pagination/Collation for Land of Oz

Inserted Title Page: Hand-lettered within a double rule border

Collation: I-I6/8, 17/4, 264 pages printed in black and white. Leaf measures 8 3/8 by 6 3/8 inches, all edges trimmed and stained yellow.

Pagination: Board lining paper printed with an illustration of the tin man and scarecrow. Publishers advertisement, introduction, copyright notice, list of chapters, dedication, subtitle for board lining paper.

Illustrations: Multiple text illustrations.

Binding: Light orange cloth, stamped in the red and green on the front, back, and spine. Cloth head and tail bands are attached to the spine ends. The spine reads from top down: The/ Marvelous/Land/Of Oz, Baum, and illustration of General JinJar and publisher Reilly and Lee.

Publication Date: July 1904

Page Layout

Page Layout

After the title page and the dedication page, there is a "List of Chapters" page. Today we use chapter numbers to indicate which section of the book we are reading. This book provides a list of chapters, but the chapters are not numbered from 1 to 24. Instead, the chapter titles are presented, and the page number where the chapter begins is present. Along the right side of the "List of Chapters" is a gallery of images of the main characters in the book, including: Tip, Jack, Mombi, Sacrecrow, Tin Woodman, Woggle-Bug and Bump. This image presentation is a creative way to show readers what characters they can expect to read about in the story. The fact that the book does not include chapters, suggests that readers would have to rely on images and titles of stories to remember which chapter they are reading. Perhaps, people referred to the page numbers as the chapter starter. Today we number our chapters, and include page numbers. Although to include a chapter number would interfere with the illumination of the text, and the incipit of the title. There is a title heading that remains on each page for that particular chapter. This heading is underlined with a thick black line. This is helpful for readers to remember which chapter they are reading.

Friday, April 6, 2012

Printer's Device- Type

Printer's Device- Type

As mentioned, Morris influenced the way books were printed and designed in Europe and America in the early 1900s. In the work, A Note by William Morris on his Aims in Founding the Kelmscott Press, William Morris recounts his printing techniques beginning with inspiration then his printing process.

"I have always been a great admirer of the calligraphy of the Middle Ages, and of the earlier printing which took its place. As to the fifteenth century books, I had noticed that they were always beautiful by force of the mere typography, even without the added ornament, which which many of them as so lavishly supplied. And it was the essence of my undertaking to produce books which it would be a pleasure to look upon as pieces of printing and arrangement of type. I had to consider chiefly the following things: the paper, the form of the type, the relative spacing of the letters, the words, and the lines, & lastly the position of the printed matter on the page. It was a matter of course that I should consider it necessary that the paper should be hand-made, both for the sake of durability and appearance" (Cockerell, p. 4).

Morris came to several conclusions when deciding how he would print, and the following points is an outline of his printing methods:

1.) Hand-made paper: wholly of linen ( In Morris' day hand-made papers were made of cotton)

2.) Hard linen that is well sized, and laid, not woven

3.) Type: Roman type

4.) Spacing

5.) Position of printed matter

The Roman type does not have any embellishments, which would make the wording easier to read. In comparing roman type to modern type, Morris believed that the letter shape should be solid, without the thickening and thinking of the line, and not compressed laterally,because it is difficult to read that way.

An example of the perfect Roman type is taken from Venetian printer of the fifteenth century: Nicholas Jenson (1470-1476). Below is Jenson's work from Laertius, printed in Venice, 1475 (Britannica).

As Morris practiced writing the Roman script, he noticed that his lower-case appeared more Gothic than Jenson's.In this case, Morris decided to design a new type that would make Gothic text more readable, then it had been before. Inspired by Chaucer's double columned book, Morris created a smaller-sized Gothic type of Pica size.Morris type was designed in 1892, and he named it the Golden type (13). The font consisted of eighty--one designs, including stops, figures and tied letters. Each type was punched out, and an retired master-printer named William Bowden acted as compositor & pressman. Below is a picture of Morris' Golden Type.

For spacing, the face of the letter should be level with the body, as to avoid white spaces between the letters. The spaces between the words should be no more than is necessary to distinguish the division into words. In other words, the spaces on all sides should be equal.

The position of the print on the page should always leave the inner margin the narrowest, the top wider, the outside edge wider still, and the bottom widest of all. This is a medieval rule used by medieval books. Morris' modern printers disagree with the idea to leave margin space because they believe that "the unit of a book is not one page, but a pair of pages" ( Cockerell, p.8) The idea of spacing and position are important features of a book, because the positioning of words can make the book more readable, or appealing to the eye.

Printer(s)

Printer (s)

There is no indication, printed in the book, that The Land of Oz was actually printed by William Morris’ Kelmscott press, but it was the most popular printing press of the time and Morris' theories revolutionized book production and typography in both Europe and United States in 1894. L. Frank Baum would be familiar with the socialist’s issues, as well as Morris’ Arts and Crafts Movement, that was popular in late nineteenth century. There were many arguments made concerning the capitalist system.

Paperback Books 1831

In the United States, the first series of paperback editions appeared in 1831. They became extremely successful after 1870. By 1885, a third of the books published were a type of popular paperback called "dime novels" because they originally cost 10 cents (Ellenbogen p. 468). The mass production of paperback books led to a decline in quality. Publishers printed many books on cheap paper. Bindings were often poorly glued, and they broke. Paperback books are an example of the kind of book production and quality that took place in the late 19th century, just before Baum published his Oz series.

William Morris- 1834- 1934

William Morris was an English poet, book designer and craftsman that led the movement for restoring the quality of printed books. Morris had always been interested in the problems of book production and longed to return to the days of the illuminated manuscript. As a book designer, he believed that the best work was always done by hand. Throughout the nineteenth century, Morris saw the history of printing as declining rapidly. In 1889, Morris worked under a printer and Socialist named, Emery Walker, and began studying the craft of printing (Wilmer, p. xxi). In 1891, Morris started producing books, in which he designed and printed fifty-two volumes, by hand, including Ruskin’s The Nature of Gothic, and the Kelmscott Chaucer. The Kelmscott is noted as the most beautiful of all printed books.

William Morris was an English poet, book designer and craftsman that led the movement for restoring the quality of printed books. Morris had always been interested in the problems of book production and longed to return to the days of the illuminated manuscript. As a book designer, he believed that the best work was always done by hand. Throughout the nineteenth century, Morris saw the history of printing as declining rapidly. In 1889, Morris worked under a printer and Socialist named, Emery Walker, and began studying the craft of printing (Wilmer, p. xxi). In 1891, Morris started producing books, in which he designed and printed fifty-two volumes, by hand, including Ruskin’s The Nature of Gothic, and the Kelmscott Chaucer. The Kelmscott is noted as the most beautiful of all printed books. Morris is known as the greatest European pattern designer since the end of the Middle Ages, because he revived the long-forgotten crafts and skills from the Middle Ages. He was successful in learning thirteen fields of decorative art including: stained glass, ceramics, painted or stenciled decoration, embroidery, wallpapers, chintzes, printed fabrics, tapestries, carpets, illuminated manuscripts, typography and book design (Wilmer, ix). His concern extended beyond the methods of design and production to his raw materials themselves: dyes, papers, inks and so on (see Printer Device post). However, he became a major authority on textile design in medieval Europe and the Middle East, as well as on illuminated manuscripts and early printed books (Wilmer, p. ix). After becoming an expert on Medieval typography, Morris wanted to motivate a happier society through the satisfactions of creative work (Wilmer, xxii). Morris seems to be the twentieth-century-scribe, who believes that hand-made materials will promote greater happiness then a machine produced copy, such as the paper back. The only problem with Morris’ theory is that he is not considering the poor population. Hand-made books take time to make. In this case, they are generally more expensive than a machine-produced copy. More people will have access to books if they are mass produced by a machine, even if the quality is bad. Handmade items would only be available to those who could afford to buy them, such as the wealthy. Morris tries to modernize an old tradition, in bringing back the idea of scribes, but it would not work in a technologically advanced society. At least with machines the poor would have some chance of reading. Despite the theory on handmade items, Morris’ design methods influenced many publishing companies.

Kelmscott Press (1890)

In 1890, William Morris created his own publishing company called the Kelmscott Press. The press was founded based on the principles of the Arts and Crafts movement. For Morris, a machine's techniques in printing lowered the standards and quality of books, and machines were developed for mass market sales. By establishing the Kelmscott Press Morris revived the Renaissance typography and book design for the twentieth-century. Morris believed that a book is a piece of architecture, each detail should contribute to the whole, so that the paper, the ink, the type-cases, the word and line spacing, the placing of the margins and the integration of illustration and decoration all had to be considered in detail, and in relation to the complete book (Naylor, p. 111). In 1890 Morris and friends established the Kelmscott Press near London. They designed and used styles of type similar to those in incunabula. They printed books on handmade paper and binding and decorated them by hand. Other printers also worked to improve thier product. Type designers such as Rudolph Koch in Germany and Fredric Goudy in the United States developed legible and beautiful types. The Kelmscott Press was Morris' interpretation of how he thought books should look. Books should be created to give pleasure to the reader based on the look and feel of the book.The combination of appearance and structure is what revolutionized book production and typography from Europe to the United States. Morris' theory on proper bookmaking inspired private presses in England, including the "Art Nouveau book" (decorative style) and decorative experiments in the 1890s. Morris layed down the foundation for good typography, as well, which many press companies individualized.

Arts and Crafts Movement

The idea of machine being a normal tool for civilization was not easy to grasp for society in the early twentieth century. Industrialization had brought total destruction to the purpose and meaning of life. Morris and his followers within the Arts and Crafts Movement saw the uncontrolled advance of technology as a threat to man’s spiritual and physical well-being, but at the same time had no clear understanding of the new industry (Naylor, p. 9). The issue seems to be that machines would be used to increase production and workers would have to work harder. Morris’ theory is contradictory because with machines it would produce more copies faster, which would allow many people to have access to people. For British idealists, mechanical progress equaled human misery and degradation. The destruction of human values were reflected in poverty, overcrowded slums, grim factories, and a dying countryside. For Morris, “men living amidst such ugliness cannot conceive of beauty, and therefore, cannot express it” (Naylor 8). The problem with industrialization would be the exploitation of the many for the profit of the few. Morris believed in a revolution , as well as other radicalsts within the design projection. By joining the cause, Morris inspired each designer to establish their own craft doctrine, which would prepare the way for Art Nouveau (creative artwork). In the movement, Morris came to the realization that machinery does not have to be a destructive force. Many designers worked for industries that supported programs for the improvement of industrial design standards.

Type Face

When the press was started the idea of having decorative features in a book was a fantastical idea. In 1888 Morris turned his attention away from manuscripts and into typography. Morris wanted to design a special type of his own in 1889 using the methods of the early printers. In 1890, Morris and friends established the Kelmscott Press near London. They designed and used styles of type similar to those in incunabula. They printed books on handmade paper and binding and decorated them by hand. Other printers also worked to improve their product. Type designers became popular in Europe and the United States, and the idea was to develop legible and beautiful types for readers.

Morris shows how important it is to learn the old ways of art, even when there are new developments in technology. Morris's ideology filtered to the United States, and since he was popular in 1900s it is an assumption that he influenced the typeset of The Land of Oz book.

Illumination and Incipit

The look and feel of Children's books is starting to change with the Oz books.

Illumination

The second book of the Oz series, Land of Oz does not include Dorothy, or the Cowardly Lion, but it introduces many of the major characters who appear throughout the rest of the Oz series. In other words, The Land of Oz revises the history of Oz to include a new wizard and to get Ozma (Tip) into the framework for the continuing stories. The first title used is The Marvelous Land of Oz: Being an Account of the Further Adventures of the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman. In this adventure, new characters are introduced. Illumination--The Land of Oz (1904)

There are various sizes of illustrations on the left and right pages of the book, including: small black and white pictures integrated into the paragraphs, small vignettes that introduce each new chapter, full black-and white plate picture outlined with a black boarder, and 16 colored plates with a black border. The idea of having color added to each page was a new concept, and color was very expensive to print. Therefore, only a few plates are in color. Baum's dream was to have the entire book have added color for every illustration. Below are a few examples of the color plates with the thick black border. Underneath each large picture (color, and black and white) is the title of the scene.

New Characters

The Woggle-Bug and Ozma are new characters introduced in The Land of Oz. The Woggle-Bug is an insect that enjoys puns. Ozma is the rightful ruler of Oz, who was hidden by the Wizard of Oz (See title post).

All of the drawings were done in pen and ink.

American Fairy Tales 1901

Baum worked with several designers/illustrators in his time for the Oz books and other fairytale books. So there are many different types of illumination revived during the early 1900s. The Land of Oz book was originally published in 1904, so the current techniques that were using near this time was illumination, and other techniques.

Baum's work entitled American Fairy Tales (1901) was produced by the G.M. Hill company. The work was a collection of twelve fantasy stories by Baum, and it was published in 1901. The designer for the collection was Ralph Fletcher Seymour (American). The first edition of AFT had an unusual and striking design: each page was furnished with a broad illustrated border done in pen-and-ink by Seymour, which took up more than half the surface of the page, like a medieval illuminated manuscript (American). This probably reflected the influence of the medieval-revival book designs produced in the late nineteenth century by William Morris at his Kelmscott Press (See Printer post). It appears that the printed book of the Renaissance was being re-vived by a team of illustrators and calligraphers--"the medieval sctipt tradition were experiencing a revival" (Avrin p. 339)

Incipit/Explicit

There are no chapter numbers to introduce the section. Each chapter is introduced with a drawing--a scene from the chapter. The drawing is done in black ink. For the title of the chapter, the font size is enlarged to appear bigger than the paragraph text. Each chapter is not outlined in a rectangle box, though, some chapters have different text format, as if Baum was experimenting with font-type. The text appears darker, in bold format. It also appears that there is larger text, or incipit, in the first letter of the title. The "T" is outlined in a square which gives the look of an old fairytale beginning (Once Upon a time...). The sizes of the title are inconsistent, possibly due to the layout of the illustrations above the text. Some chapters have smaller sized titles, and some chapters have titles that are bigger. The title is illuminated with graphics of the characters or landscape of the scene, so the size and space for the title must be coordinated with the illustration.

There are no chapter numbers to introduce the section. Each chapter is introduced with a drawing--a scene from the chapter. The drawing is done in black ink. For the title of the chapter, the font size is enlarged to appear bigger than the paragraph text. Each chapter is not outlined in a rectangle box, though, some chapters have different text format, as if Baum was experimenting with font-type. The text appears darker, in bold format. It also appears that there is larger text, or incipit, in the first letter of the title. The "T" is outlined in a square which gives the look of an old fairytale beginning (Once Upon a time...). The sizes of the title are inconsistent, possibly due to the layout of the illustrations above the text. Some chapters have smaller sized titles, and some chapters have titles that are bigger. The title is illuminated with graphics of the characters or landscape of the scene, so the size and space for the title must be coordinated with the illustration. The opening letter to the title is always larger then the rest of the title. Below is a picture of the title that has an outline of the letter "G" instead of a bold letter. The outline gives some embellishment, making the title appear more decorative than a bold letter. However, the book's chapter titles are inconsistent. The only consistency is the drawings that sit on top of the title. There is no explicit, however at the end of each chapter there is a small vignette picture that displays an illustration of the last action scene from the previous chapter.

Thursday, April 5, 2012

Title Page

FYI

When I purchased the Land of Oz book, I believed that I had the 1904 version. After researching further, I discovered that although the title page, in the book, has 1904 printed in the book, my edition is the truly the 1919 version of the Land of Oz. The following post is my confusion over the matter. At this point, I had not researched the publisher information, which clarified the difference between the two. However, it is still confusing when the publishing date is not updated.

1904 Title-Page Spread

The title page includes the title of the book The Land of Oz, an acknowledgement of the previous book: The Wizard of Oz, the author's name: L. Frank Baum, and a list of books that he has authored.

This is an oddity, to have the titles of the books that the writer has written before he has written the books. According to my research the Land of Oz was written in 1904, and the next book The Road to Oz was not written until 1909. Why, then, is it included in this title page? Many copies of this book were printed with the publishing date 1904, but the fact that the book includes the other titles suggests one of two ideas: 1.) That the stories listed would be written by Baum in the future, or 2.) that this book is a copy of the original, and published after he wrote all the books, but still has the publishing date set to 1904. In most current day books, there are many editions that have been re-issued. For instance, a book that was written in 2000, that has a new editor page, is reissued again in 2006. There would be two copyright dates, the first edition 2000, and the second 2006. For the Land of Oz book, the copyright date and the publishing date are the same, so it cannot be true that Baum authored all the books during 1904. It appears that the phrase "author of" implies that Baum has already written the books, but perhaps he has not.

The title page also includes the illustrator's name in all caps. There is a commentary "End papers from life poses by the famous comedians, Montgomery and Stone" underneath the illustrator's name.

Back of the Title page is the Copyright Information

Author's Note

The Author's note page is included after the title page. In the Author's Note, Baum discusses his inspiration for writing the book. I think this was necessary since Baum did not bleieve in sequels. The fact that small children were reqesting that he continue, suggests that children enjoyed reading his work--that he was, indeed, a children's author. The author's note allows writers to speak directly to thier audience.

Dedications

In the dedication section, Baum awknowledges the comedians. David C. Montgomery and Fred A. Stone were American actors who played the Scarecrow and the Tin man.

I am assuming that the copy that I have is not the true 1904 version, even though the copyright date states 1904. The Reilly & Britton Company published The Land of Oz in 1904, but the company changed its name to Reilly and Lee in 1919. The title page of the book includes the publisher's name as Reilly & Lee, not Reilly and Britton. I am now assuming that the copy I have is the 1919 version. According to website rareozbooks.com, before changing its name, Reilly & Britton company published 11 first editions Oz titles. Under its new name, Reilly and Lee continued to publish new Oz books and reprint older titles in the series. My question is, why did they not change the copyright date of the books? Why not change the copyright date to 1919, or add a new edition. The only difference in the book is the publisher's name. I have learned not to rely on the publication/copyright date only to determine the authenticity and history of the book. Perhaps the listing of many different titles that Baum has authored is another clue to detecting the true edition of the book.

Place of Publication

Chicago 1891-1900

The Great Fire 1871

Chicago is located in Illinois, and it first became a city in 1837. In 1891, Chicago was America's second largest city.Today, it is considered to be the third largest city in the United States (New York and Los Angeles) , and the world's leading industrial and transportation center (Duis p. 420). The city was known for providing good jobs for European immigrants, who traveled to work in factories, steel mills, and shipping business. In the late 1800s, Chicago became an industrial and commercial city. This all began after the destruction of the city. In 1871, there was the Great Chicago Fire, that destroyed most of the city. The fire forced thousands of people to flee away from the flames, which started by a cow who kicked over a lantern in a barn (Duis, p.435). The fire killed many people and destroyed much of the buildings and property worth millions of dollars. In this case, the city had to be re-built. This prompted the need for invention, and gave architects the opportunity to design an entire city using new styles and construction. In addition, this re-building to the city offered more jobs, because they needed workers to help build the city. More people came to Chicago for work, but this quickly turned to overcrowdeness, and this is when in 1893 Chicago became the second largest city in America. From this, Chicago became the nations architectural capital (Duis, p. 435).

Chicago is located in Illinois, and it first became a city in 1837. In 1891, Chicago was America's second largest city.Today, it is considered to be the third largest city in the United States (New York and Los Angeles) , and the world's leading industrial and transportation center (Duis p. 420). The city was known for providing good jobs for European immigrants, who traveled to work in factories, steel mills, and shipping business. In the late 1800s, Chicago became an industrial and commercial city. This all began after the destruction of the city. In 1871, there was the Great Chicago Fire, that destroyed most of the city. The fire forced thousands of people to flee away from the flames, which started by a cow who kicked over a lantern in a barn (Duis, p.435). The fire killed many people and destroyed much of the buildings and property worth millions of dollars. In this case, the city had to be re-built. This prompted the need for invention, and gave architects the opportunity to design an entire city using new styles and construction. In addition, this re-building to the city offered more jobs, because they needed workers to help build the city. More people came to Chicago for work, but this quickly turned to overcrowdeness, and this is when in 1893 Chicago became the second largest city in America. From this, Chicago became the nations architectural capital (Duis, p. 435).

World Fair 1893

Chicago was a progressive city that had attracted a large number of artists, architects, writers, and publishers. In 1893, the World's Columbian Exposition opened in Jackson Park, and would celebrate their progress in the largest world fair event. They would honor Christopher Columbus arrival in America (400th anniversary), but fair was more focused on celebrating the city's accomplishments (Duis. 435). A complete city was designed and built to accommodate the fair, so that the new marvels of technology were displayed in a setting that showed what a city could be (Rogers, p. 46). The early 1900s was a time where technology was celebrated, much like the 21st century, where computers and the Internet were celebrated as an improvement, or in other words progression to a more modernized world. In Chicago, the fair would exhibit new and exciting advancements in technology including electricity. Electricity was new for Americans in the 1900s. At the fair, there was an Electricity Building with a model home showcasing an electric stove, washing machine, carpet sweeper, doorbell, fire alarm, and lighting fixtures; two of Thomas Edison's latest inventions were on display: 1.) phonograph and 2.) Kinetoscope (motion picture machine) (Rogers, p. 46). Henry Ford was inspired by an "combustion engine" at the fair, believed that the engine could bring about the possibility of designing a horseless carriage, which would become the automobile. Electricity was a new idea for Americans, and they were excited about the possibilities of lighting farms, individual houses, building cities and having automatic transportation. Only 8 percent of American homes were wired for electricity in the 1900s (Rogers, p. 46). The character Dorothy, lived on a farm but enters a fantastical world where lights are illuminating an entire city. Many Americans were influenced by this World Fair. In the 1900s, the world was advancing technologically, which must have influenced Baum's writing the Wizard of Oz. In the story, there is a city called "The Emerald City of Oz" which highlights the most advanced architecture and magical beings. The combination of magic and technology seems to represent the history of the 1900s.

Chicago was a progressive city that had attracted a large number of artists, architects, writers, and publishers. In 1893, the World's Columbian Exposition opened in Jackson Park, and would celebrate their progress in the largest world fair event. They would honor Christopher Columbus arrival in America (400th anniversary), but fair was more focused on celebrating the city's accomplishments (Duis. 435). A complete city was designed and built to accommodate the fair, so that the new marvels of technology were displayed in a setting that showed what a city could be (Rogers, p. 46). The early 1900s was a time where technology was celebrated, much like the 21st century, where computers and the Internet were celebrated as an improvement, or in other words progression to a more modernized world. In Chicago, the fair would exhibit new and exciting advancements in technology including electricity. Electricity was new for Americans in the 1900s. At the fair, there was an Electricity Building with a model home showcasing an electric stove, washing machine, carpet sweeper, doorbell, fire alarm, and lighting fixtures; two of Thomas Edison's latest inventions were on display: 1.) phonograph and 2.) Kinetoscope (motion picture machine) (Rogers, p. 46). Henry Ford was inspired by an "combustion engine" at the fair, believed that the engine could bring about the possibility of designing a horseless carriage, which would become the automobile. Electricity was a new idea for Americans, and they were excited about the possibilities of lighting farms, individual houses, building cities and having automatic transportation. Only 8 percent of American homes were wired for electricity in the 1900s (Rogers, p. 46). The character Dorothy, lived on a farm but enters a fantastical world where lights are illuminating an entire city. Many Americans were influenced by this World Fair. In the 1900s, the world was advancing technologically, which must have influenced Baum's writing the Wizard of Oz. In the story, there is a city called "The Emerald City of Oz" which highlights the most advanced architecture and magical beings. The combination of magic and technology seems to represent the history of the 1900s.

Chicago is located in Illinois, and it first became a city in 1837. In 1891, Chicago was America's second largest city.Today, it is considered to be the third largest city in the United States (New York and Los Angeles) , and the world's leading industrial and transportation center (Duis p. 420). The city was known for providing good jobs for European immigrants, who traveled to work in factories, steel mills, and shipping business. In the late 1800s, Chicago became an industrial and commercial city. This all began after the destruction of the city. In 1871, there was the Great Chicago Fire, that destroyed most of the city. The fire forced thousands of people to flee away from the flames, which started by a cow who kicked over a lantern in a barn (Duis, p.435). The fire killed many people and destroyed much of the buildings and property worth millions of dollars. In this case, the city had to be re-built. This prompted the need for invention, and gave architects the opportunity to design an entire city using new styles and construction. In addition, this re-building to the city offered more jobs, because they needed workers to help build the city. More people came to Chicago for work, but this quickly turned to overcrowdeness, and this is when in 1893 Chicago became the second largest city in America. From this, Chicago became the nations architectural capital (Duis, p. 435).

Chicago is located in Illinois, and it first became a city in 1837. In 1891, Chicago was America's second largest city.Today, it is considered to be the third largest city in the United States (New York and Los Angeles) , and the world's leading industrial and transportation center (Duis p. 420). The city was known for providing good jobs for European immigrants, who traveled to work in factories, steel mills, and shipping business. In the late 1800s, Chicago became an industrial and commercial city. This all began after the destruction of the city. In 1871, there was the Great Chicago Fire, that destroyed most of the city. The fire forced thousands of people to flee away from the flames, which started by a cow who kicked over a lantern in a barn (Duis, p.435). The fire killed many people and destroyed much of the buildings and property worth millions of dollars. In this case, the city had to be re-built. This prompted the need for invention, and gave architects the opportunity to design an entire city using new styles and construction. In addition, this re-building to the city offered more jobs, because they needed workers to help build the city. More people came to Chicago for work, but this quickly turned to overcrowdeness, and this is when in 1893 Chicago became the second largest city in America. From this, Chicago became the nations architectural capital (Duis, p. 435).World Fair 1893

Chicago was a progressive city that had attracted a large number of artists, architects, writers, and publishers. In 1893, the World's Columbian Exposition opened in Jackson Park, and would celebrate their progress in the largest world fair event. They would honor Christopher Columbus arrival in America (400th anniversary), but fair was more focused on celebrating the city's accomplishments (Duis. 435). A complete city was designed and built to accommodate the fair, so that the new marvels of technology were displayed in a setting that showed what a city could be (Rogers, p. 46). The early 1900s was a time where technology was celebrated, much like the 21st century, where computers and the Internet were celebrated as an improvement, or in other words progression to a more modernized world. In Chicago, the fair would exhibit new and exciting advancements in technology including electricity. Electricity was new for Americans in the 1900s. At the fair, there was an Electricity Building with a model home showcasing an electric stove, washing machine, carpet sweeper, doorbell, fire alarm, and lighting fixtures; two of Thomas Edison's latest inventions were on display: 1.) phonograph and 2.) Kinetoscope (motion picture machine) (Rogers, p. 46). Henry Ford was inspired by an "combustion engine" at the fair, believed that the engine could bring about the possibility of designing a horseless carriage, which would become the automobile. Electricity was a new idea for Americans, and they were excited about the possibilities of lighting farms, individual houses, building cities and having automatic transportation. Only 8 percent of American homes were wired for electricity in the 1900s (Rogers, p. 46). The character Dorothy, lived on a farm but enters a fantastical world where lights are illuminating an entire city. Many Americans were influenced by this World Fair. In the 1900s, the world was advancing technologically, which must have influenced Baum's writing the Wizard of Oz. In the story, there is a city called "The Emerald City of Oz" which highlights the most advanced architecture and magical beings. The combination of magic and technology seems to represent the history of the 1900s.

Chicago was a progressive city that had attracted a large number of artists, architects, writers, and publishers. In 1893, the World's Columbian Exposition opened in Jackson Park, and would celebrate their progress in the largest world fair event. They would honor Christopher Columbus arrival in America (400th anniversary), but fair was more focused on celebrating the city's accomplishments (Duis. 435). A complete city was designed and built to accommodate the fair, so that the new marvels of technology were displayed in a setting that showed what a city could be (Rogers, p. 46). The early 1900s was a time where technology was celebrated, much like the 21st century, where computers and the Internet were celebrated as an improvement, or in other words progression to a more modernized world. In Chicago, the fair would exhibit new and exciting advancements in technology including electricity. Electricity was new for Americans in the 1900s. At the fair, there was an Electricity Building with a model home showcasing an electric stove, washing machine, carpet sweeper, doorbell, fire alarm, and lighting fixtures; two of Thomas Edison's latest inventions were on display: 1.) phonograph and 2.) Kinetoscope (motion picture machine) (Rogers, p. 46). Henry Ford was inspired by an "combustion engine" at the fair, believed that the engine could bring about the possibility of designing a horseless carriage, which would become the automobile. Electricity was a new idea for Americans, and they were excited about the possibilities of lighting farms, individual houses, building cities and having automatic transportation. Only 8 percent of American homes were wired for electricity in the 1900s (Rogers, p. 46). The character Dorothy, lived on a farm but enters a fantastical world where lights are illuminating an entire city. Many Americans were influenced by this World Fair. In the 1900s, the world was advancing technologically, which must have influenced Baum's writing the Wizard of Oz. In the story, there is a city called "The Emerald City of Oz" which highlights the most advanced architecture and magical beings. The combination of magic and technology seems to represent the history of the 1900s. Tuesday, April 3, 2012

Introduction

Introduction

After L. Frank Baum's success from his children's book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), which was a national best-seller, Baum was encouraged by children and publisher's to write a sequel. Baum did not intend for his work to be a series, but he received many requests from children to continue the stories, as included in his "Author's Note":

After L. Frank Baum's success from his children's book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), which was a national best-seller, Baum was encouraged by children and publisher's to write a sequel. Baum did not intend for his work to be a series, but he received many requests from children to continue the stories, as included in his "Author's Note":"I began to receive letters from children, telling me of their pleasure in reading the story and asking me to "write something more" about the Sacrecrow and the Tin Woodman. At first I considered these little letters, frank and earnest though they were, in the light of pretty compliments; but the letters continues to come during succeeding months, and even years." (Baum, p.3)

Thus, the birth of his second novel, The Land of Oz (1904), the sequel to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900). Baum's Wonderful Wizard book is considered to be one of the most famous stories ever written for children. The sequel is also considered to be equally as good as the first novel.

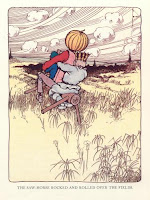

The Land of Oz- The Story

The Land of Oz is very different from The Wizard of Oz, because there is no interplay between the fantasy world and the everyday world. Dorothy does not return to Oz, so most of the action takes place in Oz, which is a fantasy land. However, the main character is a human, a mischievous boy named Tippetarius (usually called Tip), from the purple Gillken Country. Tip's guardian is a wicked witch named Mombi. At the beginning of the story, Tip escapes from Mombi, and walks to visit the King, the Scarecrow. Tip travels with a pumpkin-headed man, named Jack, with a body made of wood, that Tip made himself. With Mombi's secret powder he brings the pumpkin-man to life, as well as a Saw-Horse. When they get to Oz they must escape from an army of girls, led by General Jinjur. These girls steal emerald jewels for themselves, and any men they capture are forced to perform domestic duties, such as cook, clean and attend to child care. Women are liberated, while men are domesticated, which relates directly to the issues of the time period—women’s suffrage, the struggle for equality. The rightful ruler of Oz is a girl named Ozma who was hidden by her father, the real Wizard of Oz. Later, Glinda forces Mombi to tell the truth where Ozma is hiding. Mombi tells Glinda that she turned Ozma into a boy named Tip. Tip agrees to be changed back into his natrual form, and transforms into Ozma, who is then crowned the rightful ruler of Oz, with Glinda as her powerful ally. Oz is then taken over by females (Carpenter, p. 45).

The Land of Oz is very different from The Wizard of Oz, because there is no interplay between the fantasy world and the everyday world. Dorothy does not return to Oz, so most of the action takes place in Oz, which is a fantasy land. However, the main character is a human, a mischievous boy named Tippetarius (usually called Tip), from the purple Gillken Country. Tip's guardian is a wicked witch named Mombi. At the beginning of the story, Tip escapes from Mombi, and walks to visit the King, the Scarecrow. Tip travels with a pumpkin-headed man, named Jack, with a body made of wood, that Tip made himself. With Mombi's secret powder he brings the pumpkin-man to life, as well as a Saw-Horse. When they get to Oz they must escape from an army of girls, led by General Jinjur. These girls steal emerald jewels for themselves, and any men they capture are forced to perform domestic duties, such as cook, clean and attend to child care. Women are liberated, while men are domesticated, which relates directly to the issues of the time period—women’s suffrage, the struggle for equality. The rightful ruler of Oz is a girl named Ozma who was hidden by her father, the real Wizard of Oz. Later, Glinda forces Mombi to tell the truth where Ozma is hiding. Mombi tells Glinda that she turned Ozma into a boy named Tip. Tip agrees to be changed back into his natrual form, and transforms into Ozma, who is then crowned the rightful ruler of Oz, with Glinda as her powerful ally. Oz is then taken over by females (Carpenter, p. 45).  The fact that a boy transforms into a girl, suggests that Baum is commenting on the equality of men and women. The women's suffrage movement took place in the 20th century, and must have effected the author's writing. The book suggests that girls are equal to boys: "girls are not the same as boys, but they are not inferior, and basic identity is not determined by sex" (Rogers, p. 126). There is another "personal" instance that could have influenced the boy-girl theme. Since Baum and his wife Maud never had any daughters, it may be assumed that they longed for a daughter, which might have inspired the story to be written with a transformation from boy to girl. This story was written just before the 1920s; and by the 1920s, the gender lines were blurring. In dress style, women took a more masculine look, chopping their hair into a bob cut, and wearing fashion that resembled men's clothing--all that was popular, yet forthcoming.

The fact that a boy transforms into a girl, suggests that Baum is commenting on the equality of men and women. The women's suffrage movement took place in the 20th century, and must have effected the author's writing. The book suggests that girls are equal to boys: "girls are not the same as boys, but they are not inferior, and basic identity is not determined by sex" (Rogers, p. 126). There is another "personal" instance that could have influenced the boy-girl theme. Since Baum and his wife Maud never had any daughters, it may be assumed that they longed for a daughter, which might have inspired the story to be written with a transformation from boy to girl. This story was written just before the 1920s; and by the 1920s, the gender lines were blurring. In dress style, women took a more masculine look, chopping their hair into a bob cut, and wearing fashion that resembled men's clothing--all that was popular, yet forthcoming.References

References

American Fairy Tales. Wikipedia Accessed 15 April 2012 from

Avrin, Leila. (1991). Scribes, Script and Books. ALA Classics. 356 pages. ISBN: 978-0-8389

1038-2.

Basten, Fred E. Glorious Technicolor: The Movies' Magic Rainbow. Easton Studio Press, 2005.

Baum, L. Frank. (1919). The Land of Oz: A Sequel to The Wizard of Oz. Chicago: Reilly and

Lee.

Carpenter, S. Angelica and Jean Shirley. (1992). L. Frank Baum: Royal Historian of Oz.

Lerner.144 pages. ISBN: 0-8225-4910

Duis, R. Perry. Chicago. World Book Encyclopeida. p. 420-437. Chicago: World Book, Inc.Ellenbogen, Rudolph. Book. (2007). World Book Encyclopedia. p. 468. Chicago, IL.

Wilmer, Clive. William Morris: News From Nowhere and Other Writings. Penguin, 2004. ISBN: 0-140-43330-9

Edith Van Dyne," Aunt Jane's Nieces Abroad, Chicago, Reilly & Britton, "1906" [1907].

“George M. Hill.” Inland Printer (Maclean-Hunter Publishing Company) 59: 692. 1917.

Greene, L. David and Dick Martin. (1977). The Oz Scrapbook. New York: Random House.

Maxine, David. Hungry Tiger Press (Blogspot).

Morris, William. (1984). The Kelmscott Press: 1891 to 1898: A Note by William Morris on his

Aims in Founding the Kelmscott Press. The Typophiles, Inc. London City Council.

Naylor, Gillian. (1971). The Arts and Crafts Movement. Massachusetts, The Mit Press.

Parisi, Paul (February 1994). "Methods of Affixing Leaves: Options and Implications". New

Library Scene 13 (1): 8–11, 15.

Reilly & Britton Accessed 5 April 2012 from http://www.rareozbooks.com/published.htmlReilly, O. Michael. (1997). Oz and Beyond: The Fantasy World of L. Frank Baum. University

Press of Kansas. 286 pages.

Riley, O. Michael. (2011). A Bookbinder’s Analysis of the first Edition of The Wonderful Wizard

of Oz.). The Book Club of California, San Francisco.

Rogers, M. Katharine. (2002). L. Frank Baum, Creator of Oz: A Biography, New York, St. Martin's

Press. pp. 143-4, 273 n. 53.

Roman script. [Photograph]. In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from

Weigand, Steve. (2001). U.S. History for Dummies. New York: Wiley.

Wilmer, Clive (Ed.). (1993). William Morris: News From Nowhere and Other Writings. Penguin.

"World's Columbian Exposition" Encyclopedia of Chicago . Accessed 5 April 2012 from

Zacharias, Gary. (2004). 1900-1920: The Twentieth Century. New York: Thomson/Gale.

Sunday, April 1, 2012

Context

Women in Men's World 1869

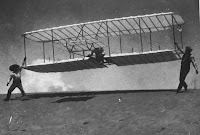

The Wright Brothers 1903

In the early twentieth century, feminists were still seeking the right to vote. In 1869, African-American men were given the right to vote through the Sixteenth Amendment while women of all races were still excluded. Women recognized one ideal: universal emancipation. The idea was that once the Civil War was won by the North, and the Union was preserved, African Americans would be enfranchised as voting citizens, and woman would naturally gain the same rights. However, after the war was over and slavery was abolished, the women's rights movement was betrayed. Along with white men, black men who pushed for change in the constitution decided to cut off funding for any efforts to win the vote for women (Schwartz p.30). The Fourteenth Amendment, which protected the citizenship of black men, specifically defined as "male" which prompted the 15th Amendment, which guaranteed black men, as citizens, the right to vote. Women lacked the opportunity to vote, and be recognized as citizens. The women of the United States, denied for one hundred years the only means of self-government--the ballot--are political slaves (Schwartz, p. 39). Women did not get the right to vote in all of the Western states. In July of 1917, the woman's suffrage movement went to the extreme. A team of women suffragist tried to storm the White House. These women were arrested, but President Woodrow Wilson pardoned them because he was sympathetic to their plight. A constitutional amendment--the Nineteenth--was submitted to the states, and in 1920, it gave women the right to vote in every state.

The Wright Brothers 1903

William and Orville Wright were two brothers from America who changed the world with their vision of flying through the sky. The Wright brothers owned a bicycle business in Dayton, Ohio in 1892. There were many bicycles but none with wings built. The Wright brothers went to Kitty Hawk, North Carolina and developed the world's first powered, sustained, and controlled flights with a machine they had built (Weigand, p. 222). The Wright brothers finally realized their vision of powered human flight in 1903 (Zacharias, p.56). The airplane revolutionized the entire world, families could cross the ocean in a short time. However, the airplane was also used to tear families apart, and making international warfare more possible. The airplane revolutionized international business, and travelers were set on a path that would lead beyond Earth. The Wright Brothers Fly the First Heavier-than-Air Craft: December 17, 1903.

Henry Ford 1903

Henry Ford Establishes a Car Manufacturing Company in 1903. Ford built the Model T, which is considered the first affordable car for the common person. He pioneered assembly-line production techniques that drove down the price of his cars. Ford revolutionized automobile production. He provided a more affordable car for common people. Ford inspired other car makers, and both changed American lifestyle. An average family could travel, which created a new sense of independence and self-esteem. By the end of the 1920s, it could be argued that the automobile had become the single most dominant element in the U.S. economy (Wiegand, p 221).

Arts and Crafts Movement

The idea for the Arts and Crafts movement began with the promise to maintain traditions of art until the time when true craftsmanship and social production would be indistinguishable. The goal was to restore labor and eliminate alienation. The idea that machines would be able to mass produce items faster, was a major concern for the founder of the movement, William Morris. Society had to be reconstructed to view art as a necessity. Morris strived to revive the hand production and prove that craftsman could be progressive. The main reason for the movement was a response to commercialism " they rebelled against the turning of men into machines, against artificial distinctions in art, and against making the immediate market value, or possibly of profit, the chief test of artistic merit" (Morrison, p. 13). In other words, Morris and his followers believed in supporting the artistic work of designers and craftsmen. Morris' leaders included a designer Walter Crane and bookbinder T. J. Cobden-Sanderson. They each considered themselves socialists. The Arts and crafts movement strove to return to handicraft methods and avoid competitive commercial management; arts and crafts would bring art into the everyday work of the industrial classes, humanizing and beautifying the industry in the process (Morrison, p. 14).

The Oz Series

Wizard of Oz (1899-1900)

The first book in the Oz series in entitled The Wizard of Oz and is written by L. Frank Baum, and illustrated by W.W. Denslow. This book introduces readers to the land of Oz, through the experiences of a little girl named Dorothy Gail. Baum's work is considered a fairy tale and an original story because it focuses on two entirely different lifestyles 1.)"the grim naturalistic picture of a poor Midwestern farm," "the vastness of the prairie, its lack of trees, its drought, its loneliness, its liability to cyclones, and the effects of these conditions upon those who lived there, (Rogers, p. 73) and 2.) the magical, technological "Emerald City of Oz". The Emerald city is the fantasy portion that appears to represent the current day White City--the 1893 Columbian Exhibition in Chicago, that was later torn down. The exhibition was meant to show people what an ideal city could be. This is what the first Oz book represents two different lifestyles: the grey town of Kansas, and the new green and colorful town of the Emerald City. Baum's Emerald City is a fantasy city, just as the White City was a fantasy, a glimpse of the future for Americans.

Education

The Land of Oz was published in 1904, which is a time where children were heavily educated: "Educators thought that children should read realistic books with useful lessons" ( Carpenter, p. 133). The Oz books were not considered educational, but rather fairy tale books with no importance. In this case, the Oz books were censored from the very on site of the series. So, how could the books be so popular (best-selling children's book), if the books were censored? These books reflect today's fantastical series--Harry Potter. There was much controversy when the book was published, and many schools banned the book for its witchcraft theme. According to Carpenter, in Baum's lifetime, fantasy was unpopular, especially in the early 1900s. Librarians of the period believed that series books were bad, because "if a child read one Oz book, that child expected to read them all!" Many libraries i in history banned the Oz books:

1957

"Florida State Librarian Dorothy Dodd made news when she listed Oz and other series as "poorly written, untrue to life, sensational, foolishly sentimental and consequently unwholesome for the children in your community" (Carpenter, p. 134).

1980s

Critics called the Oz series offensive. Many characters from The Patchwork Girl were stereotypes of African Americans.

1986

Christian families filed suit against publish schools for having The Wizard of Oz books as required reading in elementary classes. The parents did not want their children reading about witches. They also felt that the female characters were assuming male roles, and animals were elevated to human status. Luckily, the judge ruled that the book will stay in the schools, and that the parents can remove their children from classes where the materials were used.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)