L. Frank. Baum

Lyman Frank Baum was born on May 15, 1865 in Chittenango, New York. His father and mother were German immigrants, who moved to America for religious freedom. Baum's father went into the oil business and made a fortune. Baum was the seventh child (out of 9) born to his mother Cynthia Ann Stanton. In Angelica Shirley Carpenter’s biography, L. Frank Baum: Royal Historian of Oz, she describes Baum’s physical problems; he had a weak heart, and suffered all his life from "angina pectoris," which caused severe chest pains (p. 14). In his father's library, Baum learned how to read. He also had private tutors, because he was not allowed to over exert himself, due to his heart condition. Baum's favorite books were written by British authors including Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray, and fairytales. While Baum enjoyed reading fairytales, he also critiqued them, "One thing I never liked then, and that was the introduction of witches and goblins into the story. I didn't like the little dwarfs in the woods bobbing up with their horrors" (Carpenter, p. 14). Baum’s parents often comforted him after a nightmare, because fairytales were too frightening. For this reason, Baum promised to create a new style of fairytales, one that would not consist of any horror.

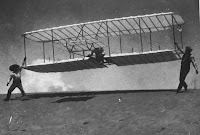

"Tell us a story!" "A story right away now!" said a group of children (Carpenter, p. 9). Baum was a storyteller before he became a children’s book writer. He would tell stories to local children, which was his own way of developing his ideas for The Wizard of Oz. The children loved to hear stories about talking animals. The more he re-told his stories, the more his characters began to develop. Baum noticed the reaction of amazement in the children's faces as he told them the story and he enjoyed making up stories for entertainment. According to Baum's son, Frank Jr., the name Oz came to Baum as he was telling a group of children about Dorothy, the Scarecrow, and the Tin Woodman on May 7, 1898 (Carpenter p. 10). When a child asked him where these adventures were taking place, he glanced at his file cabinet, noticed that the last drawer was labeled O-Z, and replied "Oz" (Rogers, p. 89). Baum was known for making up good stories for children, interviews, and more. His nephew Henry B. Brewster mentioned that "he always likes to tell wild tales, with a perfectly straight face" --he was the most imaginative of men (Rogers, p. 89). Baum’s writing comes from an imaginative place, and he lived during an era where many imaginative inventions took place, including the automobile, the airplane, electricity, and architecture. Baum’s Oz stories contribute to the vast amount of revolutionary inventions of the 1900s.

Baum desired to create a new type of fairytale that would not focus on the gruesomeness of the evil character. However, for the dramatic aspect of his story, he realized that he had to include some type of monster figure. The traditional fairytale of the time included 1.) A protagonist that is removed from the normal setting and has to find their own way back, 2.) Meets and helps three creatures, who in turn help the character reach their goal, 3.) Befriended and opposed by witches, good and bad, who work magic (Carpenter, p. 34). In staying with the traditional fairytale structure, Baum strove to re-invent some of the elements to make them new by:

1.) Avoiding the horrors of the Grimms' fairy tales, but including a small amount of frightening things, such as The Wonderful Wizard of Oz’s Wicked Witch of the West.

2.) Having more of the story focus on friendly and helpful characters

3.) Rescue--a traditional theme of the period, when little animals help stronger ones who have been good to them. This idea is similar to the Aesop fable Mouse and Lion.

Baum started writing at an early age, due to his fascination with printing. His father bought him a cheap printing press, and he and his brother, Harry, used it to produce The Rose Lawn Home Journal. At age 17, Baum printed more journals, and started a stamp dealership (Rodgers p. 22). Baum was already interested in the arts before writing the Oz books. From a reader, a writer, a printer, and a publisher, Baum was an entrepreneur from the very start. The printing press must have been accessible for Baum to have access at age 17. According to Scribes, Script and Books, writer, Leila Avrin highlights the Private Press Movement: “its proponents, who considered the book a work of art, rejected mass production and returned to handmade materials and hand-printing in a self-conscious way. They believed that high aesthetic standards could be achieved only through hand labor” (p. 338). For the late 1800s, the return to handmade products was re-invented—a return to the medieval “scribe days”. In this case, the printing press was highly popular.

Baum was familiar with printing. In the winter of 1897/1898 Baum borrowed a small press and some type, and began to print a book of his verse (Riley, 40). If printing press’ were very affordable, or easy to have access to, then this is similar to our ability to self-publish our own work today. Baum was able to borrow a press, probably from work, to work on his own projects. His first project was a book, By the Candelabra’s Glare which was distributed only among relatives and friends. But, it was the book Father Goose that became the turning point in Baum’s life.

There were many radical ideas formulating in the 1900s, and Chicago’s world fair was developed to present these ideas. In Baum' s older years, he was drawn to Chicago by the world's fair. In 1896, Baum met an illustrator named William Wallace Denslow, who illustrated for the Chicago Herald Denslow agreed to collaborate and illustrate them for a children's book (Carpenter, p.47).

Father Goose (1899)

Color printing was a radical idea in the late 1800s. Together, Baum and his illustrator, Denslow were the first to think of including color to illustration in children’s books. For the Father Goose books, they wanted to include color to each page of illustration, but this idea would make it hard to sell. In the late 1800s, illustrations were usually black and white. Color printing raised the price of a book, and lowered publisher's profits.

However, Baum and Denslow found a publisher named George M. Hill who agreed to print the book with color illustrations. Baum and Denslow were to pay the entire cost of publishing for the book, but later, Hill decided to share in the expenses. Together as author and artist, they shared the cost of production with the Hill Company (See publisher post). Baum's Father Goose appeared in 1899. The book is a re-invention of the Mother Goose Rhymes, which are a collection of fairy tales and nursery rhymes. The Father Goose book sold 75,000 copies in the first year, which made it the bestselling children's book of 1899 (Carpenter, p.50).

The Father Goose book design is beautiful. Every page is a picture printed in flat poster colors of red, gray, and yellow. In his book Oz and Beyond: The fantasy World of L. Frank Baum, Michael O. Riley, mentions that the lavish use of color was rare in American children’s books of the time (p. 41). The verses are hand-lettered in large, easy-to-read print by a Chicago artist named Ralph Fletcher Seymour. This is the example of innovative book design of the period. The popularity of Father Goose was a combination of factors: Denslow’s illustrations are simpler and funny than the characters in Mother Goose.

The fact that it became popular could be due to the new idea of adding color to the illustrations. On the other hand, Baum’s verse could be what kept the tales interesting. According to Carpenter, the critics of the period felt that Denslow's pictures were better than Baum's verse. This is an interesting notion, because the creativity aspect is shared and working closely with another person could mean that ideas for a story developed based on someone’s creativity. This leads to further questions about the creation of the Oz books. When an author and writer share credit in their work—who should take full credit for the book? Baum or Denslow? Was the story written after the illustrations were drawn, or before?

After the publication of the Father Goose books, Baum and Denslow shared the profit from the success of the book. Baum and Denslow, next, decided to work on their second book together, entitled The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900). Hill was not enthusiastic about publishing another book using color printing, because it was too expensive. The subject matter was also rejected because there were too many fairy-tale books already in print. However, Hill gave in and agreed to publish the book under the same publishing conditions at the Father Goose book. Baum and Denslow had to supply all the printing plates, and Hill would only print and distribute the book (Riley p. 42). Another successful collaboration, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900) became the best-selling children’s book of 1900. However, Baum and Denslow had several arguments over the copyrights of the illustrations, becuase Denslow published his own "Father Goose" using the characters that were created by Baum "Frank was outraged because he considered the Father Goose characters to be his invention" (Carpenter, p. 61). Baum and Denslow never collaborated on any other work together again, after Wizard of Oz (1900). (See illustrator post)

After publishing The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), Baum was motivated by friends from the Hill Company, Sumner Britton and Frank Reilly, to write a sequel. From then on was the birth of the Oz series, beginning with sequel entitled The Marvelous Land of Oz. Baum wrote a total of thirteen Oz books, and collaborated with a new illustrator John. R. Neill.

From storyteller, to printer, to author, Baum had many of his own creative ideas, but they were strengthened by the illustrators that he worked with. Because of Baum's wild imagination he thought about the concept of color that was used in the story as well as in the production of the book. Since many children were delighted in his storytelling abilities, I believe that it is truly Baum's writing that has kept the story a classic today, not necessarily the illustrations.